ON A DRIPPY October Saturday in 1973, I’m standing, cornet in hand, with 145 fellow members of the Franklin Community High School marching band, preparing to step onto the field.

Or more accurately, into the field. Here at the walled Southport High School football stadium—a regional site for the inaugural All-State Marching Band Contest—the turf has already been pounded into pudding by the several-hundred high-stepping feet that came before us. We begin our performance on a mucky plain where the white yard lines have been trampled beyond recognition, our feet sling mud like mini monster trucks, and a 90-degree turn can become a slippery 360.

Nine minutes later we unleash our brassy finale, “My Way,” and exit the field minus an array of scattered shoes and majorette boots. But in the daylong saga of band versus nature, we keep our composure as other schools lose theirs, punching our ticket to the finals of the first true state marching band championship in Indiana history.

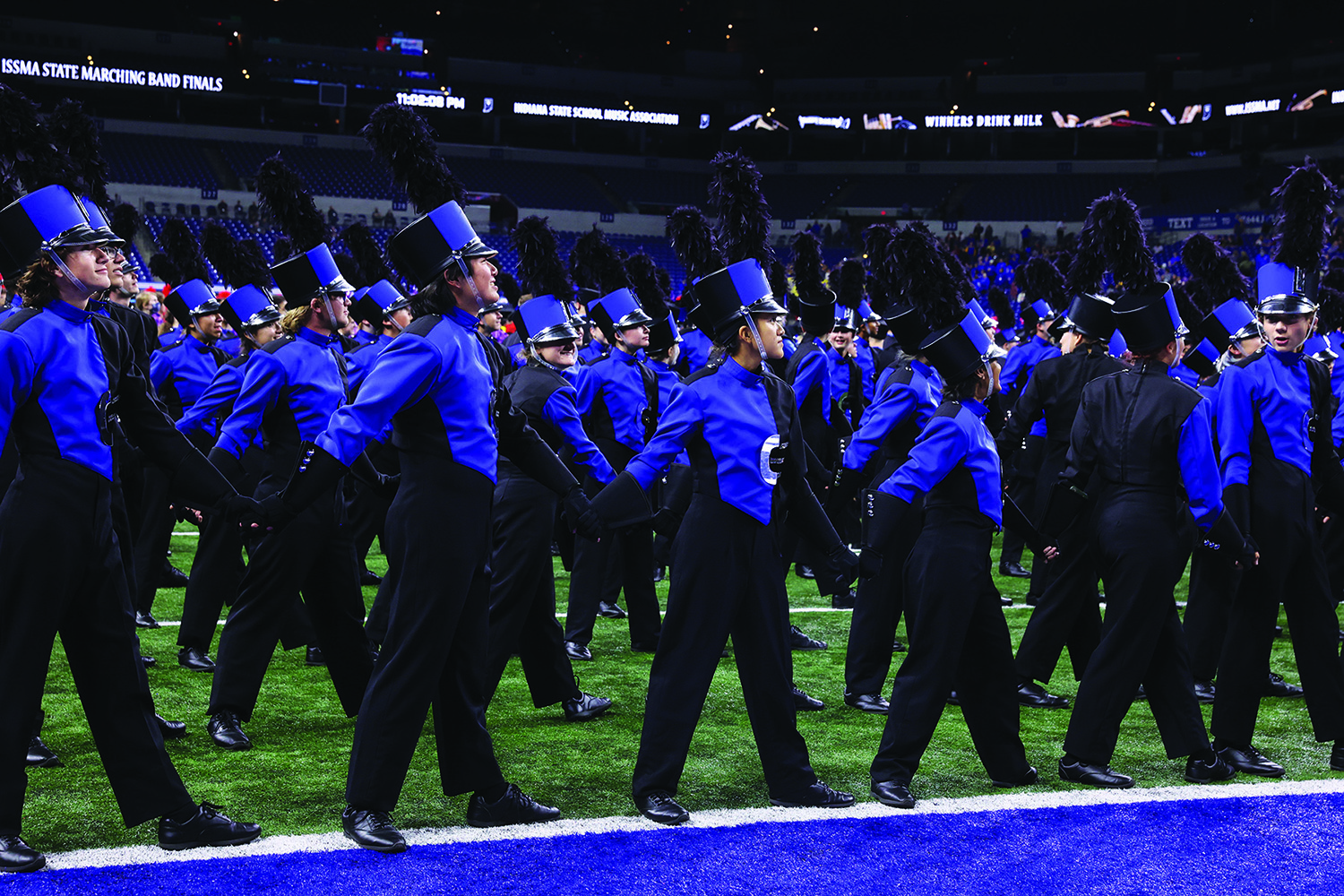

Today, the state marching band finals aren’t soloing anymore. Two other major marching music makers also crown their champions in Indy. Bands of America arrived in the same year as the Hoosier (later RCA) Dome in 1984. Its Grand Nationals annually attract about 100 bands, including many of the nation’s high school heavyweights. (Civic pride moment: Carmel and Avon finished first and second in 2022; three other Indiana bands made the finals—Brownsburg finished in eighth, Fishers in 10th, and Castle in 12th.) In 2008, Indy managed to snare Drum Corps International, which bills itself as “marching music’s major league.” Unlike most marching bands, DCI involves independent drum and bugle corps from across the country. Band members are 14 to 22 years old, prospects must ace an audition, and woodwinds need not apply. This gives Indianapolis a trifecta of state, national, and international marching contests.

The 50 years after 1973 witnessed an evolution in the marching arts, but the 50 years before 1973 tell a forgotten tale of how we almost stifled the development of a state marching band championship in Indiana. The state showed its musical chops early when Notre Dame founded the nation’s first collegiate marching band in 1845. Purdue claimed its own first in 1907 when its marching band audaciously broke military formation to create a block letter “P.”

Illinois sparked the contest movement for high school bands in 1923 when the Chicago Piano Club sponsored a new competition, the Schools Band Contest of America.

Indiana quickly caught the wave. “Students from all parts of the state will assemble here for what is expected to be the greatest contest of its kind in the state’s history,” a 1926 Muncie Star Press article said of an upcoming band, orchestra, and choir competition sponsored by the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce. That same year, the first band camp in history opened near LaGrange, and band contests got a governing body, the Indiana School Band and Orchestra Association (the forerunner of today’s ISSMA). In 1927, the first authorized high school band and orchestra contests in the state took place in Elkhart, where 40 percent of the nation’s band instruments were manufactured. High school band was booming. Until 1935, when Association members separated Northern Indiana from the central and southern portion. “The Hoosier state will have two groups of music champions next year,” The Indianapolis Star declared.

This created a vacuum of statewide competitions. It wasn’t until 1947 that high school marching units got their chance to square off again at the Indiana State Fair. Only 11 bands took the first Band Day challenge, but in the ensuing years, the number of participants more than octupled, drawing an all-time high of 94 in 1962. The notion of marching band as a team sport wasn’t lost on WTTV Channel 4, which began live broadcasts. Yet, Band Day was never a true state championship. Performances were on a narrow horse racing track instead of a 100-yard football field, limiting what bands could do to show off their skills.

It would be another decade before the imaginary north-south wall dissolved with the 1973 All-State Marching Band Contest. Its significance was instant, with 98 bands statewide entering.

As we leave 1973 in the echoes of contests past, I should mention how my school finished in the All-State finals. When the day came, it was sunny, the field was grassy, the yard lines were intact, our blue uniforms stayed clean—and we placed fourth in Class B, the middle of the three divisions. We should have celebrated, but we didn’t. Only the two highest finishers in each class received trophies, so we left empty-handed.

It took me decades to fully appreciate our accomplishment. The ISSMA website lists only the top five bands in each division from 1973. So there we are in elite company, one of 15 finalists out of the total 98 bands that entered. We were the first band from our school to crack a statewide top five since Band Day 1957. And except for the crew that took fourth in 1977, no Franklin marching band after us has matched, let alone surpassed, what we achieved.

The soggy fledgling event that I experienced at age 17 marks its golden anniversary this month, and aside from the basic elements of music, marching, and a 100-yard stage, the two eras have about as much in common as sousaphones and smartphones. Let’s compare.

VENUES

The current battlefield of the bands is as major league as it gets: Lucas Oil Stadium. Sure, it was conceived as a pigskin palace, but how many other NFL venues included accommodations for marching bands in their blueprints? A warmup area and a black curtain backdrop were incorporated into the original design to facilitate music competitions. The stadium sports 67,000 seats, plus luxury suites for the full geek experience. The 2023 state marching finals on October 28 and the Grand Nationals on November 9–11 will resound beneath the retractable roof.

In 1973, our last-round showdown unfolded on a grassy gridiron quaintly known as Space Pioneers Field. The Indianapolis Public Schools facility, which hosted the games of Northwest High School (now a middle school), reportedly got the gig because of its “excellent viewing tower for watching the program.”

TRANSPORTATION

The truck stops here. “Pretty much every band has at least one semi,” says Mick Bridgewater, executive director of the Indiana State School Music Association, which oversees the state finals. “In the ’70s, you might have had a U-Haul. Now, some bands need three, four, or five semis [to haul gear].”

INSTRUMENTATION

Searching for a violin player on a marching field was the 1973 equivalent of a snipe hunt. But today’s high school bands employ a variety of instruments that would never have been seen, let alone heard, at the first state finals—such as electric guitar, timpani, synthesizer and, yes, violin. Even singing won’t get your band banned.

THE MUSIC ITSELF

“In the ’70s and ’80s, and even in the early ’90s, directors picked maybe three pieces that they thought were cool,” explains Mark Middleton, ISSMA instrumental education director. “Now, there’s a theme to the show.” In the 1973 state finals, Anderson High School’s selections included Ringling Bros. circus music, “Eleanor Rigby,” and the title song from How the West Was Won.

FIELD SHOWS

Back in the day, raised steps and snappy 90-degree turns defined the marching genre. Today, field performers move quickly and constantly. It’s like watching a lava lamp with legs.